Many Muslim victims continue to live in Internally Displaced People camps, still dreaming of returning home.

RANGOON, Myanmar

It’s been one year since a Buddhist mob rampaged through the central Myanmar town of Meiktila, killing local residents and setting fire to their homes. Today, the violence is over, but many of the Muslim victims continue to live in Internally Displaced People (IDP) camps, still dreaming of returning home.

The violence started after a mob attacked a Muslim-owned gold shop in the center of Meiktila following a dispute. Later that evening, a Buddhist monk was dragged off a motorbike and beaten by a group of Muslims. He later died in hospital.

Over the next two days over 40 people were killed by the mob, which also set about destroying Muslim homes, setting fire to mosques and attacking religious schools.

“They brought them out and killed them with swords,” said Thin Thin OO – an eyewitness to the violence. She told the Anadolu Agency that she was standing by the Muslim madrassa, having just got off her moped, when three students were brought out.

“All of the children were hit in the neck,” she said, as she placed the side of her straightened hand on her neck to illustrate a chopping motion. “One of the children was hit on the neck with a sword. He dropped to the ground but they carried on hitting him. They just didn’t stop.”

OO is Muslim, but she may have been left unscathed as there was no visible way the mob could determine her faith. It’s impossible to distinguish many Muslims and Buddhists, bar a beard, a hijab or other visible symbols of faith.

The memories, however, remain.

“The Buddhists were calling the children ‘Kalars,’ they were saying: ‘Don’t leave anyone, finish off all the Kalars’,” she said.

“I remember the children begging the Buddhists to let them go – they (the children) were around 16-years-old.”

One year on, she is still haunted by the moment, adding that she still sees some of “the murderers” around town.

Eighteen-year-old Assad Ullah was a student at the Madrassah. He said he still remembers what happened.

“We were hiding, and the police came to take us to safety, but when we came out and walked through the Buddhist area, the Buddhists attacked us,” he told the AA.

He said that his attackers were armed with knives and swords, and launched themselves at them in full view of the police who were helpless to do anything.

“The Buddhists told us to worship them… They said ‘if you worship us, you will be saved,'” he said. “Some did and (yet they) were still killed.”

He said he remembered one of his teachers – Maulana Shafi – refusing to bow down to the mob and being killed before his eyes.

“He was beaten and stabbed; he was still alive when they poured petrol on him and set him on fire.”

Ullah started to cry at the memory of the day: “Everyone ran, whoever was found was killed,” he said. “I was lucky.”

By the time police intervened and the shaken Muslims were taken to the station four teachers were missing and 30 students had been killed.

“I think about it a lot… It is hard to study now… It’s hard to bear. It is very hard to deal with,” said Ullah.

On that note, Ullah suddenly stopped talking, the pain of the memory clearly too much, our conversation coming to an abrupt end.

Two days later, with the town smoldering, the military intervened and declared martial law. What was left of the homes was a trail of destruction with thousands of Muslims displaced.

The properties destroyed in the center of Meiktila are still to be rebuilt, leaving many victims unable to return, their homes reduced to burnt-out rubble.

Those whose properties were not destroyed and have felt that it is safe to return have done so, while others have gone to live with relatives or remain in the IDP camps, where they are dependent on aid from charities such as the World Food Programme. In the town center. mosques remain closed and only a handful of businesses operate.

Tint Hetw, 70, sits outside the Chan Aye Tha Ya mosque in Meiktila. There have been attempts to rebuild the homes around it, but the mosque still stands.

“First a mob of around 40 people came. They had knives and sticks,” he told the AA. “Behind them were even more, thousands of Buddhists, that had come to destroy the Muslim area.”

He said that although police came to protect the Muslims “they could not do anything to stop the mob.”

Al Hajj Maulana Hanif still lives in a camp with his wife and two daughters, exactly one year after the mob burnt down his and his neighbors’ homes.

He told the AA that he was one of around 5,000 people who hid in a nearby forest as the mob laid siege, only to reappear when police arrived and said they would protect them.

“The police took us in vehicles to the police station. There were also Buddhists with us, their homes also burnt down as they lived in our area.”

Hanif told the AA that not only was his house razed, he has no job, no home, no goods to sell, and accused the government of taking their land.

“We have no solace, peace or security. We are always worrying. What is happening? What will the future hold?” he said.

Hanif lives in a government camp where journalists are denied access. There are around 1,300 displaced people there. In Yandaw, at Madinatul Uloom mosque, there are 1,200 internally displaced people. They are all reliant on aid and have been there for a year.

AA was given access to Yandaw camp as is not run by the Myanmar government, but by local Muslims.

Laila Bi — a 33-year-old resident of Yandaw — told the AA that she used to have a restaurant in Meiktila but it was destroyed during the violence.

“We put everything into our restaurant, and when it was destroyed we fell into debt. How were we supposed to pay back the money if we did not have our business anymore?” she asked.

She said her husband has also now left, leaving Myanmar and travelling to Malaysia in search for work so he can pay back the debt.

“It’s very difficult. I feel depressed all the time,” she said, tears forming at the corners of her eyes. “I feel like it (the situation) is useless.”

As she tried to wipe the tears away, camp trustee Muhammad Ali stood over her and told her things will be “OK.”

Bi’s older brother was also killed during the violence. She now lives in a small, one room bamboo hut with her four-year-old daughter. All the families live in similar huts regardless of their size.

They all want to return to Meiktila but feel it is not yet safe, and there is always a concern that the violence could start again at any time.

Ali told the AA that Muslims from around Myanmar and others from overseas had donated aid to the people in the camp, but “right now we can only give them rice and oil,” to eat he said.

There may, however, be a bigger issue at the heart of the violence.

Most of the Muslims that the AA met believed that the violence was orchestrated, and not necessarily related to the argument at the gold shop, or the beating of the monk.

“I think it was a plan to move Muslims out of the main economic area. Some Buddhists are occupying the land and hoping that they will have future market control,” said Ali.

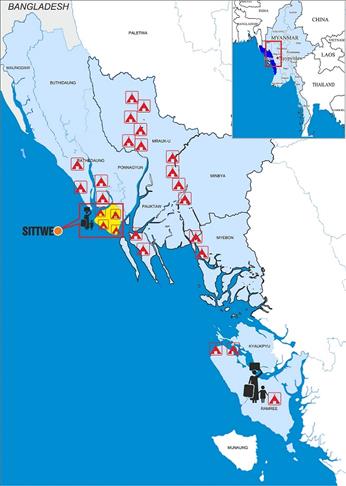

Unlike the Rohingya Muslims of Rakhine state, the Muslims of Meiktila are considered Myanmar citizens, but this does not appear to have stopped extremists from targeting them. Their businesses have been the focus of protests for some time, not least from extreme militant Buddhist monk – and leader of anti-Muslim 969 group – Ashin Wirathu, who has urged Buddhists to boycott Muslim businesses and even likened them to dogs.

Such attacks have led Myanmar’s Muslims — who make up 4 percent of the country’s population — to complain about such hate speech. They have lobbied the government to put a stop to it.

Leaflets distributed by Buddhist monks often claim that Muslims are conspiring against Buddhists with help and money from Saudi Arabia. The narrative the extremists adopt is one that Buddhism is under threat from Islam, and Buddhists must defend their faith.

Little has so far been done following the violence, however, Myanmar President U Thein Sein did touch on the subject soon after.

“I am deeply saddened to find out that a simple private dispute led to such deadly violence and those instigators, taking advantages of the disingenuousness of the public, attempted to exploit the situation to engineer violence in other parts of the country,” he said.

Read the original article published in Anadolu Agency on 20 March 2014