Ali Shan is an 90-year-old Kashmiri who spent five years in Burma fighting against the imperial army of Japan for the British.

I was greeted with a strong hand shake from him at his family home in Sparkbrook where the former soldier lives with three generations of his family.

He was wrapped in a traditional Kashmiri shawl, and wore thick glasses through which he inspected me for a minute.

Originally from Pootha in Pakistani administered Kashmir, Ali Shan says he is the last surviving member of his village that had served in Burma.

He told me that there were another eight or nine people from his village who served in the British army in Burma.

Fierce Japanese fighters

Almost deaf, Ali struggled to hear my questions but, when he did, he replied with youthfulness and a vivid sense of reminiscence in his voice.

The war against the Japanese in Burma lasted between 1942-1945.

|

Reflecting on his training he said: “First we learnt how to fire a rifle while in the frontline of attack.”

Then his voice fell silent as he gazed past me for a moment then, in a lower tone of voice, he continued: “We saw many dead…. many dead people, children and men.”

Ali remarked that many of those who served the British were from very poor families.

His army career in Burma lasted five years without returning to his family in Pakistan.

Problems with communication

“It was difficult,” he reminisced. “The Japanese were fierce fighters,” he added with respect.

“There was no mixing between the white officers in charge and the Indian soldiers. How could we learn English? We were not even allowed to speak to the white soldiers.”

“The only English word I remember is attack!” Ali shouted out the word: “Attack!”

Ali feels let down and that these soldiers from the Empire are not remembered, feeling their contribution and valour is little recognized in modern-day Britain.

“The British of those days saw themselves as very superior beings and had little regard for inferior ‘natives’ such as us,” Ali reflected ruefully.

In the context of a debate about “Britishness” Ali may not be considered as being very “British” by many.

Medals for valour

He speaks very little English and dresses in traditional Pakistani attire but he did give five years of his life fighting for the British against the imperial army of Japan.

The Burma campaign cost more than 200,000 lives on both sides

|

Ali saw the justice in the war he was taking part in and when I asked him if he would have taken part in the war against Iraq or Afghanistan he replied: “No, that war was different. This present war is not the same thing.”

Ali Shan received eight medals for his valour. The medals are kept in his home village in Pakistan.

In his youth, Ali Shan was a traditional arm wrestler in Kashmir and was well known in his region for his strength. He came to England in 1954 where he worked in a factory for 23 years.

Hope for recognition

During the Second World War there were 2.5 million Indians who fought for the allies under the British flag in Asia, North Africa and Europe.

Thousands were killed and as many as 80,000 were taken prisoner. Black and Indian soldiers also saw action during the First World War.

Ali still lives in the hope that he will receive something from the British Government in recognition of his contribution to the British Empire.

Read the original article published in BBC on 13 November 2010

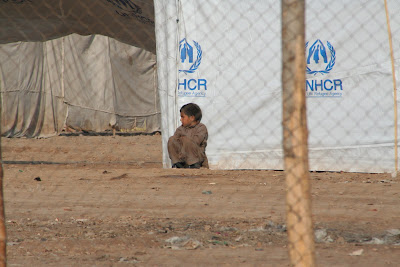

In Pakistani-administered Kashmir this small refugee camp is home to some 600 people who have fled Indian-administered Kashmir, 16km from the line of control. This is the line of the world’s most militarised zone. Since the Mumbai attacks and continued Indian allegations of Pakistani involvement tensions are once again forcing people to fortify their bunkers as they brace themselves for a potential confrontation.

In Pakistani-administered Kashmir this small refugee camp is home to some 600 people who have fled Indian-administered Kashmir, 16km from the line of control. This is the line of the world’s most militarised zone. Since the Mumbai attacks and continued Indian allegations of Pakistani involvement tensions are once again forcing people to fortify their bunkers as they brace themselves for a potential confrontation.